How to: Create WCF 2 Plugins

Customizing your WBB4 / WCF2 installation is usually done via plugins. Editing files, following bogus installation and hacking instructions, this is all long gone. Since WBB3, which was built on top of WCF1, hacking is obsolete and was replaced by simply installing plugins via mouse-click in the ACP. The general principle is the same for WCF2 as it was for WCF1, but some detailes have changed.

So what is a plugin?

Basically, just a TAR- or TGZ- archive that contains

some files in a specific structure. The heart of each plugin is the

package.xml, a configuration file which defines the plugins dependencies and

it’s delivered functionality. The package.xml file is placed in the root of

the plugin archive.

A typical package.xml

Typically, a package.xml would look like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<package name="org.example.wcf.plugin" xmlns="http://www.woltlab.com" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.woltlab.com http://www.woltlab.com/XSD/maelstrom/package.xsd">

<packageinformation>

<packagename>WCF2 Example Plugin</packagename>

<packagedescription>This plugin is used for demonstrational purposes.</packagedescription>

<version>1.0.0 Alpha 1</version>

<date>2013-08-09</date>

</packageinformation>

<authorinformation>

<author>Sebastian Teumert</author>

<authorurl>http://www.teumert.net/wcf/</authorurl>

</authorinformation>

<requiredpackages>

<requiredpackage minversion="2.0.0 Alpha 1">com.woltlab.wcf</requiredpackage>

</requiredpackages>

<instructions type="install">

<instruction type="file">files.tar</instruction>

<instruction type="template">templates.tar</instruction>

<instruction type="language">language/*.xml</instruction>

<instruction type="option">option.xml</instruction>

<instruction type="eventListener">eventListener.xml</instruction>

</instructions>

</package>

So what is this all about? In the first line, the XML version and encoding is

specified. This is pretty straight-forward. In the next line, the package

identifier is specified, in this case org.example.wcf.plugin. You can call

your plugin whatever you like, but the accepted standard is to use the scheme

tld.domain.(wcf|wbb|<sa>).<plugin>, where <sa> stands for an arbitrary

standalone application. If you don’t know (yet) what it means, don’t worry, you

can wrap around your head around that later, and <plugin> somehow further

categoryzes your plugin. For example, if you happen to write a FooBar

bbcode, you could name your plugin tld.domain.wcf.bbcode.foobar.

The remaining attributes, namely xmlns, xmlns:xsi and xsi:schemaLocation

just specify that this XML file follows the structure that is appropriate

for an package.xml.

Inside the <packageinformation> block, the package name as it can be read in

the package list in the WCF is specified, along with a brief summary of the

funtions of the plugin (e.g. “Provides a FooBar BBCode with uses the FooService

to bar the baz”), the date of creation and the version number. Similarly, the

<authorinformation> block is quite self-explaining.

Requirements

Now, the first block that probably needs a more in-detail explanation is the

<requiredpackages> block. In this block, you specify the dependencies of

your plugin. This means that the package is required for your plugin, meaning

it has to be installed in the version specified as minversion, or higher.

Obviously, the first package to be declared is almost ever com.woltlab.wcf

or, if you write a WBB plugin, com.woltlab.wbb. You should take a good look

at which packages are needed for your plugin to work and require them here.

There is also the possibility to exclude incompatible packages - but more on that will come in a separate article.

Instructions (PIPs)

Your plugin will most likely try to deliver some functionality - this is

where the <instructions> blocks come into play. There are two types of

instructions - install and update, with the obvious semantics. You can

specify various update instructions, each with a different fromversion

attribute to handle updates from other versions of your plugin to the

current, but you should only declare one (1) install block.

Functionality is delivered via so-called PackageInstallationPlugins (PIPs). There are three types of PIPs: file-based, XML-based and script-based PIPs.

File-based PIPs usually log which files they delivered and integrate those files into the installation, e.g. The File-PIP or the Template-PIP (as well as the ACP-Template-PIP). The Files- and Template-PIP are therefore the two most important PIPs inside WCF.

XML-based PIPs extract the delivered XML files and configure the installation

accordingly. you can for example deliver new ACP options via the Options-PIP,

new user group permissions via the UserGroupOptions-PIP and more. Sometimes

PIPs have correlations, for example if you deliver an EventListener (EL) via the

EventListener-PIP (an XML-based PIP), you need to include the proper PHP

class file in which the code of your EL resides in the Files-PIP.

The Language-PIP is a kind of special PIP, because it does not specify

a single XML file, but allows you to use wildcards in order to recognise

XML files for various languages at once.

The last class of PIPs are the script-based PIPs. They are rarely ever used, mostly only during installation or major updates. They allow you to specify additinal scripts that should run during installation or update, making it possible to do adjustements in the installation that were otherwise impossible (e.g. rewriting the database structure and keeping the data intact when the new version of your plugin has a heavily altered database structure). There is also an SQL-PIP, that allows you to deliver custom .sql files that have to be executed upton installation. I considers this to be also an script-based PIP.

A small sample plugin

Now, let’s create a small sample plugin that adds a new static page to your WCF installation. Later on, we will also add an item to the page menu and read some data from the database that we will display.

The package.xml

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<package name="org.example.wcf.page.helloworld" xmlns="http://www.woltlab.com" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="http://www.woltlab.com http://www.woltlab.com/XSD/maelstrom/package.xsd">

<packageinformation>

<packagename>Hello, World!</packagename>

<packagedescription>A variant of he Hello, World! sample for WCF 2.0</packagedescription>

<version>1.0.0 Alpha 1</version>

<date>2013-06-08</date>

</packageinformation>

<authorinformation>

<author>Sebastian Teumert</author>

<authorurl>http://www.teumert.net/wcf/</authorurl>

</authorinformation>

<requiredpackages>

<requiredpackage minversion="2.0.0 Alpha 1">com.woltlab.wcf</requiredpackage>

</requiredpackages>

<instructions type="install">

<instruction type="file">files.tar</instruction>

<instruction type="template">templates.tar</instruction>

</instructions>

</package>

Pretty straigtforward, huh?

Creating our own page class

The next thing to do is to create our own page. In WCF, all pages have to implement

wcf\page\IPage, but for simplicity we can also extend wcf\page\AbstractPage, which

provides a sane base implementation for wcf\page\IPage (Note that interfaces start

with a capital “I” by convention). Furthermore, A pages name has to end on Page and

it has to be located inside the folder wcf\lib\page\. Thefore, it has to be in the

wcf\page namespace. This is due to how the auto-loader of WCF works, it maps namespaces

to folder directly. Furthermore, all PHP files inside WCF can only contain one class

and are named ClassName.class.php. This means that our page will be called

HelloWorldPage inside the wcf\page namespace, will extend AbstractPage and will

be saved under lib\page\HelloWorldPage.class.php.

And this is how it would look like:

<?php

namespace wcf\page;

use wcf\system\WCF;

/**

* Shows the Hello, world! page.

*

* @author Sebastian Teumert

* @copyright 2013 teumert.net

* @license

* @package org.example.wcf.page.helloworld

*/

class HelloWorldPage extends AbstractPage {

}

And that is it. We do not override any of the methods of AbstractPage here, since

we do not need it (yet). Later on, we will override assignVariables() to activate

our own page menu item, override readData() to read some data from database and

much more.

Note that we also did not specify a template here. This is due to the auto-detection

used withing WCF. You can specify your own template by using the class member

$template, but we can rely on the auto-detection feature here which will use the

helloWorld template for our page automagically.

A simplistic template

For a simple template, the boilerplate is quite extensive, it should – in general – look like this:

{include file='documentHeader'}

<head>

<title>Hello, world! - {PAGE_TITLE|language}</title>

{include file='headInclude' sandbox=false}

</head>

<body id="tpl{$templateName|ucfirst}">

{include file='header'}

<header class="boxHeadline">

<h1>Hello, world!</h1>

</header>

{include file='userNotice'}

<p class="info">My first WCF page!</p>

{include file='footer'}

</body>

</html>

Save this in templates\helloWorld.tpl.

For testing purposes, we don’t even need to create a plugin. Lets say WCF_DIR

is the directoy in which you have a working development version of WCF 2.0, then you

can simply copy the HelloWorld.class.php to WCF_DIR\lib\page\HelloWorld.class.php

and the template to WCF_DIR\templates\helloWorld.tpl and your page will be available

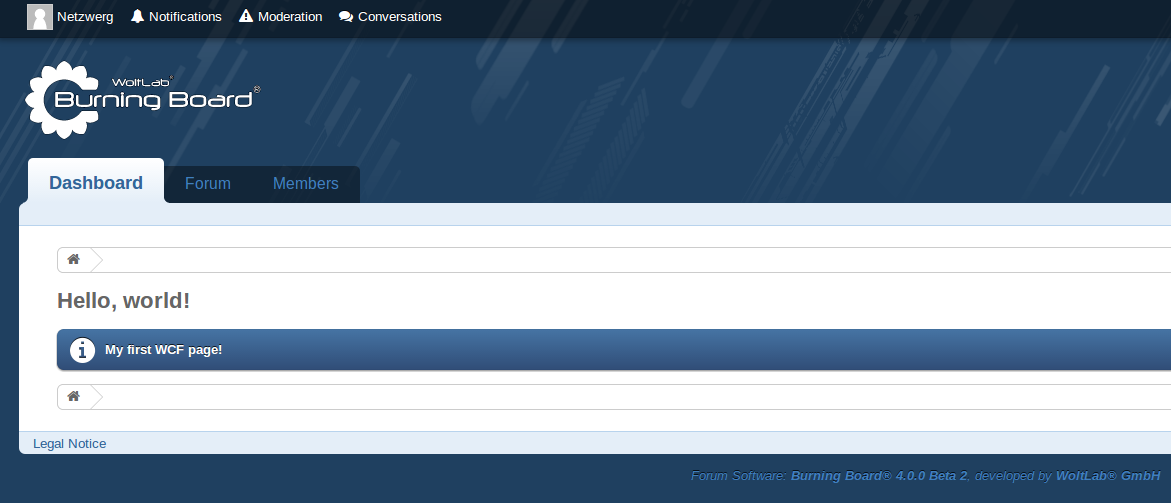

under index.php/HelloWorld/ and should look like this:

Creating the plugin

Now, moving files into an exsiting installation is the hacky way, and it will not

work once XML- or script-based PIPs come into play. Fortunately, we already made

a package.xml in order to be able to deliver our files as a installable plugin.

Fortunately, building a plugin is quite easy. You only need to place the

HelloWorldPage.class.php inside a TAR archive (by convention, it should be named

files.tar. Keep in mind that you will need to preserve the directoy structure,

e.g. you will need to have it placed inside lib\page\ inside the archive.

Then simply pack your template into a separate TAR archive (by convetion, this should

be named templates.tar).

At last, pack the files.tar, templates.tar and package.xml in an archive and

you are done. You now have an installable package. You can download an already packed

reference version of this plugin under

downloads/org.example.wcf.page.helloworld.tar.

Organizing development smart and building packages automagically

At this point I want to point out wmake, a shell script that I’ve written to automagically build WCF packages.

If you structure your plguin according to WCF standards, you can use wmake to generate the TAR archive with all relevant files auomatically. Read the linked article about those standards, they make life much, much easier.

Next steps

In the next few days I’ll post articles in which the base page is extended. At first I’ll discuss using language variables and delivering them instead of hard-coding text in the template, followed by page menu item and activation, and an article about reading data from database and displaying it, as well as an in-depth overview about WCF 2.0 different built-in page types.

Further Information

If you have further questions, tweet me, open up a discussion in the WBB4 beta forums or the WSF (I read both boards and answer questions about plugin development regularly there), or file an issue on GitHub.